REFUGEE CAMP & ARRIVAL IN PARIS

In my refugee camp

Picture of my mother and 5-year-old me. Shohid Nagar, 50 km from Kolkata was a remote slum-like refugee camp without electricity, potable water or sanitation facilities. I was born here in 1954 because my family fell victim to India’s violent religious division in 1947, and became penniless overnight.

What led to refugee camps

After World War II, three unrelated incidents constrained the British monarch to grant freedom to India. The newly formed United Nations compelled its members like the UK, among others, to give up their colonies. In the UK, the Labour party came to power in 1945 with a promise to end colonisation. And in India, growing unrest erupted among Indian personnel in Britain’s armed forces. Over 2.3 million Indian soldiers had been conscripted for the 2 World Wars, and almost a million had died fighting for their colonial masters.

Demoralizing independence

After 200 years of atrocious colonization, the British gifted Independence to India. But within those 200 years they demoralized Indians into subjugation. By banning industrial activity, they left India devoid of skill and dependent. Yet they had the ability to leave behind an aura to British superiority which Indians still respect. They created a new country called Pakistan by bizarrely carving out the Muslim dominated areas of India. So East Bengal became East Pakistan and West Punjab became West Pakistan although the 2 land sections were separated by 2200 kms of Indian territory.

Religious separation

Consequently, a religious bloodbath broke out. So india’s independence was based on religious separation. Over a million died when about 18 million Hindus were deported to India from what became Pakistan, a new country.

Escape to Shohid Nagar

In this mindless mayhem, my family from Dacca Bikrampur had no choice but to flee East Bengal (which is now Bangladesh) to West Bengal in India. My 21-year-old father along with his mother, younger siblings and other East Bengalis forcibly evicted from their homes, chose to squat in Shohid Nagar tents. They avoided Kolkata’s overcrowded slums.

My family history

Seated at left is my great grandfather Ruhini Sengupta in western dress wearing the Raisaheb medal which the British Crown honoured him with. Seated on the right is my grandfather Chittaranjan Sengupta in Indian dress. Behind them are the 3 other sons of Ruhini Sengupta. This picture was probably taken after World War I.

This is a flashback story I’ve heard from my grandmother and father. During WW1, my great-grandfather Ruhini Sengupta was a civil engineer in Burma for the British Empire. He helped build several strategic infrastructures. For successfully accomplishing his jobs, the British rewarded him with the title of honour called Raisahib. He established himself as a very wealthy person in Rangoon, and enlarged the family’s landed estates in Dacca, Bikrampur. Of his 5 sons and 4 daughters, my grandfather, Chittaranjan Sengupta was the eldest.

About my grandfather

Chittaranjan Sengupta was against British colonization of India. As a renowned advocate in Insein in Burma, my grandfather would spend his mornings in court fighting to defend revolutionary political prisoners. In the afternoon he worked for his business clients. He was a very wealthy person who kept his family in the lap of luxury. But he died abruptly at the age of 39 in 1936, leaving behind his wife and 10 children. My father, his eldest son, was 10 years old when my grandfather died.

About my grandmother

The sudden death of my grandfather turned my grandmother Nalini Bala’s life upside down. Being young and helpless, she had to give up the big luxurious house with multiple cars that she lived in with her husband in Insein. She took her children to the family home in Dacca and lived a very modest life there. So during India’s bloodstained independence in 1947, my grandmother and her children had to run away overnight from their home from Dacca to India for fear of getting butchered in the political turmoil of that time.

My mother, my art enabler

My mother Nila recalls that I was just 3 or 4 when art possessed me. Living in a mud house where its thatched roof and bamboo walls would fall apart in the face of any gusty wind or monsoon storm, it seems my only obsession was to draw with a stick on the mud-floor. Or with chalk or a piece of brick I would draw on any surface I found conducive. I have no idea what ambition my mother had for me, but she was my unflinching supporter, saying “Never forsake your art.”

Overcome poverty

Our neighbours would warn her against encouraging my passion for art; she would listen, but never reply. Looking back, I remember her golden words, “Poverty should not empty your emotion, creativity, hygienic sense and civic sense.” I was fascinated by the art activities of my fellow East Bengali artisan refugees. I would watch them hand-craft shell bangles, terracotta tea cups, mud dolls, idols and decorative items in our refugee camp, and learn from them.

My father, my art influencer

My father, Apurba Ranjan Sengupta was a sharp intellectual. His knowledge about art, culture and world politics influenced me to gather knowledge about France. He said lots of foreign artists had come to France to work. Here their colour palette was reversed to become bright, and they subsequently became famous. France, he told me, was the only country that nurtured artists, giving them total freedom of expression.

Twice dislodged from home

But my father, who was twice ousted from his home, used to feel totally victimised. He had lived luxuriously with his father in Insein, then led a mediocre life in Dhaka, and finally fell into the squatted Shohid Nagar refugee camp. He often said to me that this big fall had irreversibly broken his life, so he can never build any career. He became a working-class leader fighting for the rights of the poor. My mother, the only breadwinner in our family with meagre earnings as a local school teacher, never accepted that.

Dare to take risks in life

She always encouraged me to build a life with my passion for art. As I was born into poverty, I have not experienced it as trauma like my father did. Somehow my mother had taught me to be bold, daring and take risks. That prompted me to abandon my Kolkata art studies unfinished and adventure on to France at age 19 with just $8 in hand.

Arrival in Paris

It was a cold winter day on 19 November 1973 when I landed at Orly airport, Paris. My first mission was to see Louvre Museum. I requested a tourist in Paris to take this picture of me in front of the Louvre. I had no money to enter inside, but just seeing it was a climax for me.

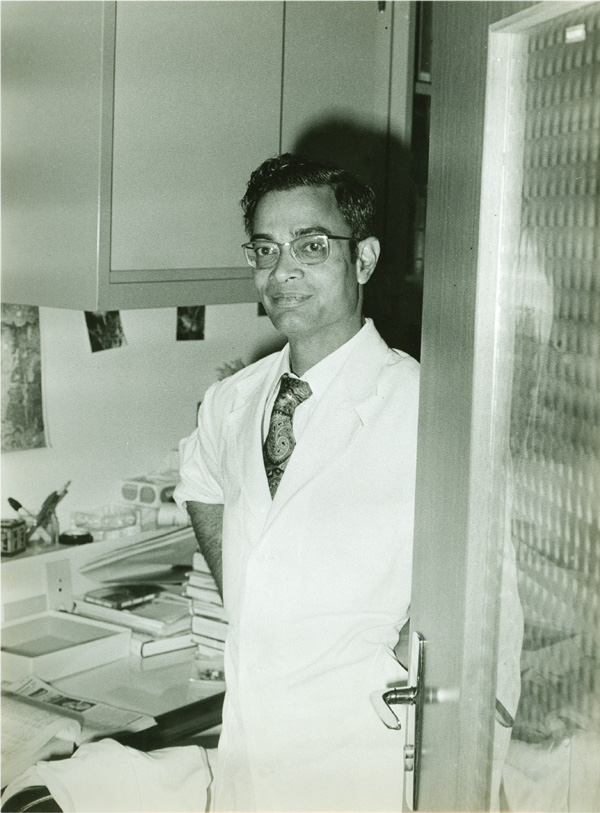

Finding Dr CK Pyne

French CNRS scientist Dr CK Pyne, originally of Chandannagar, West Bengal, in this laboratory at 105 Boulevard Raspail, 75006 Paris.

The incredible generosity of Dr CK Pyne is indelibly etched in my brain. I had arrived in Paris without any rationale of what will happen tomorrow. I knew nobody in France, knew no French, had no place to stay. With only $8 and my academic artwork dossier from Kolkata, I was dreaming to become a painter in France. Even the airport’s moving walkway was a shock for me. Seeing me perplexed and hesitate, a kind French stewardess held my hand to step on it. I had heard the name of a Bengali scientist, Dr CK Pyne, who worked in CNRS in Paris. With lots of communication difficulty I found his name and address in the French telephone directory. I reached his office at 105 Boulevard Raspail 75006 Paris.

Grand generosity

Dr Pyne had no idea who I was. I was excitedly telling him about my search for art as he was looking through my art dossier. Then he looked at me. I felt he was highly seduced. I remember he was feeling very uncomfortable to see me shivering with cold and without an overcoat. I just had a thin jacket. He took me to his house. He told me I could stay there till I find a job. What a great gesture! If I hadn’t found him that day, or he hadn’t so kindly given me shelter, I don’t want to wonder what would have become of me!

Following my gut feel

Dr Pyne gave me his old overcoat and 200 francs. You can see me wearing his coat in this picture. The courage I got from his support to an unknown painter like me, from only seeing my drawings, was immeasurable. I told him I would do any kind of job to become an artist in France. He was convinced and said, “Follow your gut feel.” The fuel of confidence Dr Pyne bestowed on me continues to remain with me. I can still feel it in my present life. This is the way my Parisian journey started.

Some people call it a fairy tale

My journey in France started 1973 as a penniless dreamer seeking art. From being a sweeper I went on to studying in the most famous Parisian art college to establish myself as a painter and designer. Because I felt responsible to also support my big family, I was obliged to become a designer to earn a regular income at an early stage. By injecting the imaginative techniques I had acquired in my fine art studies, I got the opportunity to work as a brand strategist and designer for several Fortune 500 companies across 5 continents. During my corporate life I used to paint 50 paintings a year and have exhibitions from time to time. Since 2015 I have devoted myself totally to my artistry, painting 150 paintings a year. I am ever grateful to my passionate art collectors, and am overwhelmed to have had exhibitions at The Louvre, The Grand Palais, and in many prestigious places in the world.